As part of my ongoing not-all-that-regular series on Kickstarter, today I want to take a look at the wide world of Stretch Goals.

As part of my ongoing not-all-that-regular series on Kickstarter, today I want to take a look at the wide world of Stretch Goals.

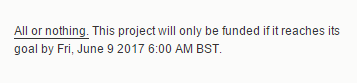

As I explained in the Kickstarter Basics article, every KS project comes with a Funding Target – The Funding Target of a pledge would generally be (more-or-less) the minimum amount that designers have worked out they need in order to actually make the game – the costs of making the bits and pieces, and getting them out to the buyers: you don’t want to pitch it too high, because if you set the bar at $100,000 and people pledge $99,999, then you don’t get a penny, the whole thing fails.

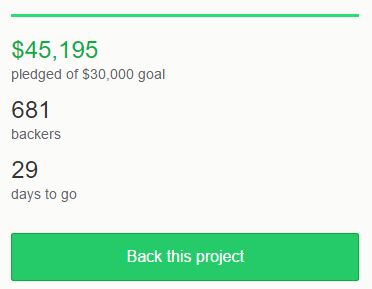

On other hand, if you hit $100,000 on day 15 of 30 (or 5 minutes into day 1 for some projects…), what happens then? Whether you’re a designer who believes they have a great game that people deserve to know about, or simply a business looking to make more cash, chances are that you aren’t just going to think “job done” – you want more people to keep coming along and backing the project for the rest of the funding period. To make that happen, a lot of people turn to stretch goals.

On other hand, if you hit $100,000 on day 15 of 30 (or 5 minutes into day 1 for some projects…), what happens then? Whether you’re a designer who believes they have a great game that people deserve to know about, or simply a business looking to make more cash, chances are that you aren’t just going to think “job done” – you want more people to keep coming along and backing the project for the rest of the funding period. To make that happen, a lot of people turn to stretch goals.

A stretch goal is a sort of unofficial extra target for a KS project- they’ve already hit the funding target, so the project is going to happen, but this is a way to keep people engaged, and hopefully make it all bigger and better.

Making it Better

Maybe you launch a project for a game, and set a target of $20,000 – as soon as you pass $20,000 you know you can make your game. Maybe if you got $25,000 you could use a higher-quality card-stock, so you add that as a stretch goal. If you get to $30,000, the dice included could be custom dice rather than generic ones. At $40,000 maybe you have enough cash to make 20 different cards for each deck in the game, instead of 15.

In an attempt to keep driving traffic to the Kickstarter page, many projects will drip-feed the stretch-goals: announce 1 or 2 to begin with and, as the targets are met, those goals are “unlocked” and you can announce the next one – this keeps people coming back to check in on things, and generates a buzz around the game.

More cynically, it allows designers time to re-balance if funding goes a lot better (or worse) than anticipated, but however you look at it, it helps generate a sense of progression. Lots of projects will have late stretch goals that the designers always planned to include, but they announce them just before the end, in order to provoke a late surge in funding.

Money for nothing

(NB: All the numbers quoted in this section are hypothetical)

There are always issues with stretch goals, and one major issue is cost.

Imagine you launch a project where the game costs $40, and you have a funding target of $20,000. Assuming no optional purchases/wonky international shipping charges etc, that’s 500 backers you need to get funded. Imagine if, instead, you get 1000 backers. That’s $20,000 more than you were expecting. However, you now need to produce 1000 copies of the game, not just 500.

This is where it gets complicated. It probably doesn’t cost twice as much to produce twice as many copies of the game – you still only need the same number of pieces of art, the same number of designers, and the factory still has the same amount of set-up work to do. Equally, it doesn’t cost the same to produce 1000 copies as 500 – you need twice as many raw materials, you have twice as many boxes to ship etc.

On this basis, you probably have some money to offer extras as stretch goals. Let’s say that the original $20,000 was $10,000 of art, design, set-up costs, and $10,000 of raw materials and shipping. Your 1000 backers have increased your revenue by $20,000 dollars, but only increased your costs by $10,000 – that’s $10,000 spare.

But what do you do with that $10,000? – say you decide to have extra art, or commission nicer art from your favourite artist – $5,000 more spent on art probably has no real impact on your ongoing production costs. However, if you decide to upgrade that card-stock, it’s a different matter: if you improve materials, you impact the whole of the project – instead of $20 per copy on materials, you’re now spending $25 – that’s not just $2500 on components for the first 500 copies, but $5 for every extra copy you sell. This means that for all future stretch goals, you’re working with a reduced margin, as each new pledge of $40 now only brings you $15 to play with, not $20.

But what do you do with that $10,000? – say you decide to have extra art, or commission nicer art from your favourite artist – $5,000 more spent on art probably has no real impact on your ongoing production costs. However, if you decide to upgrade that card-stock, it’s a different matter: if you improve materials, you impact the whole of the project – instead of $20 per copy on materials, you’re now spending $25 – that’s not just $2500 on components for the first 500 copies, but $5 for every extra copy you sell. This means that for all future stretch goals, you’re working with a reduced margin, as each new pledge of $40 now only brings you $15 to play with, not $20.

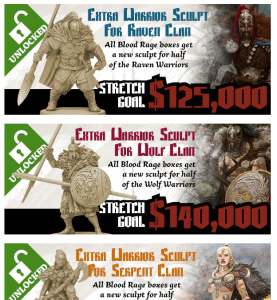

A lot of this has to do with economies of scale, particularly with Miniatures games. Broadly speaking, to make a miniature for a game, you need to spend a fair amount of money paying an artist to sculpt it. Then you need to spend a fair amount more on getting a mould made to cast it in plastic. Once you’ve done that, actually squirting plastic into the mould probably costs a fairly trivial sum

Using hypothetical numbers, you might need to spend $250 to get the sculpt crafted, another $245 on a mould, but be able to produce copies of that new figure for $0.50 a time. If your campaigns raise figures somewhere in the millions of dollars, you can offer a stretch goal like “extra sculpt for miniature x” with a fairly static cost: you hit your sculpting and moulding cost as a 1-off, but then have no additional materials cost for making 3 figures each in 2 poses as you previously had for 6 figures all in the same pose.

If you’re adding figures, rather than simply adding variety, the costs are still small – up until they aren’t. Even if it only costs you $0.50 for a single miniature, Rising Sun, CMON’s most recent Kickstarter received over 30,000 backers – that’s $15,000 to give each backer 1 extra miniature, using our hypothetical figures. By the time you reach a certain level, even if the per-unit cost is very low compared to the static set-up cost, you have a very limited amount of slack in the budget. That’s why most Kickstarter projects will see the stretch-goals spaced further and further apart as the pledge total gets higher.

Numbers?

As I mentioned above, all of the numbers I’ve used here are hypothetical. I don’t know how much it costs to commission a sculpt, or to move from sculpt to cast to mould, or to make a figure once you have all your moulds ready to go. I’m pretty confident that the start-up costs are much higher than the ongoing ones, but I don’t know the numbers. I’m not claiming to be an industry insider, nor an expert, and I hope that no-one goes away from this (or any of my other) article(s) having been mislead in any way.

– since writing this, I’ve found This Interesting Article, which isn’t really looking at the same thing, but is still interesting in terms of money, numbers and board-games.

The problem though with the internet in general, and Kickstarter comment sections and forum discussions in particular, is that everyone’s an expert. You can confidently expect dozens of folks with no experience of miniatures casting to come along and announce to all that making X “only cost Y,” or “definitely cost at least Z” – maybe some of them are right, but a lot of them won’t be, and this can lead to a lot of bad-feeling as backers feel that the creators of the project are simply profiteering, rather than ploughing the money back into the game. This is particularly problematic, because there’s a chance it might be true – some Kickstarter creators are small, independent start-ups, desperate to get their game to market, and incredibly grateful to anyone who has helped realise that dream. Others are multi-million-dollar companies for whom the goodwill of the buying public is just a resource like any other, to be judiciously managed on the road to maximum profit – they’ll give stretch goals where it will help drive sales, but never so that it’s going to cost more than it generates.

Great Expectations

Big Board Game Kickstarters have been a thing for several years now, and people have expectations. They expect stretch goals, and if it’s an established company like CMON, they will have expectations for what those stretch goals should be, and how often they should come. With the sense of entitlement common to most millennials, as soon as those expectations fail to be met, you can expect them to start baying for blood.

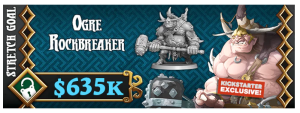

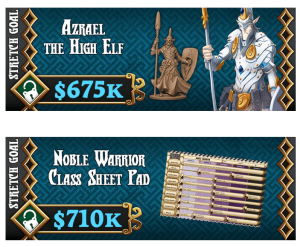

In the Massive Darkness campaign, there was a fair amount of anger when the $675k stretch goal was the Miniature for a new player-character, Azrael the High Elf, and the 710k stretch goal was the class-sheet pad for the Noble Warrior. As Azrael is a Noble Warrior, a lot of people cried foul play at this point- this was one stretch goal, they argued, disguised as 2, to give the false impression of smaller gaps between goals.

In the Massive Darkness campaign, there was a fair amount of anger when the $675k stretch goal was the Miniature for a new player-character, Azrael the High Elf, and the 710k stretch goal was the class-sheet pad for the Noble Warrior. As Azrael is a Noble Warrior, a lot of people cried foul play at this point- this was one stretch goal, they argued, disguised as 2, to give the false impression of smaller gaps between goals.

Now, CMON are big enough that they didn’t care – they knew the project was going to break a million dollars, so both goals were happening anyway. It’s also technically true that Azrael could be played as a different class, so it was technically an extra thing, even if people didn’t like it.

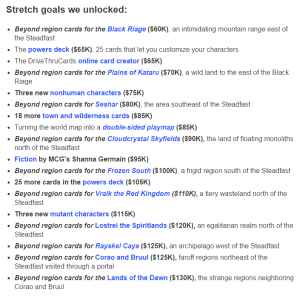

Aeon’s End is a marketplace game (think Dominion), so the Stretch Goals in their KS campaigns generally take the form of new cards for the marketplace, increasing the variety. Each time a few thousand more dollars were notched up, another card was added for backers, a spell here, a gem here. Some of these cards are now simply part of the game, whereas others are either Kickstarter exclusives (backers get them, others don’t), or “Promo” (backers get them at no extra cost, others may have the chance to buy them at a later point).

With 20+ stretch goals unlocked by the time the campaign ended, having raised more than 10x the original target figure, this one would have to be classed as a success.

Right?

Well, unfortunately, this campaign suffered a bit of a PR fail with one of the late-ish stretch goals.

Well, unfortunately, this campaign suffered a bit of a PR fail with one of the late-ish stretch goals.

Every game of Aeon’s End requires a set of cardboard “breaches” –the holes in reality through which player-characters fire their spells. In the original game, these were fairly thin and bendy, so people were fairly happy when the 80k stretch-goal upgraded them to thicker card-stock.

Some also commented that they would prefer their breaches with rounded corners. However, they seemed a bit puzzled when the $275,000 stretch-goal appeared, “round corners for breaches” – this seemed to put noses out-of-joint for a number of reasons: firstly they’d already “used up one stretch-goal on breaches,” secondly there was a perception that making the breach corners rounded shouldn’t cost any more than having them square [as far as I can tell, most people have now come over to the idea that it would cost more, which sounds plausible to me, although I really don’t know]. Thirdly this coincided with the gap between stretch-goals going up from $10,000 to $15,000, which most people felt warranted a more exciting reward.

There was a fair amount of grumbling and mockery in the Kickstarter comments and, aside from various jokes along the lines of “next goal: even rounder corners,” one comment in particular leapt out at me

There was a fair amount of grumbling and mockery in the Kickstarter comments and, aside from various jokes along the lines of “next goal: even rounder corners,” one comment in particular leapt out at me

“Ok I asked for round corners a while back but i dont think its SG material. Its something than you just do because its something that you do….. I dont think round corners justifies 15k really.”

Lack of apostrophes aside, it’s fairly clear what they mean – and clear that they’re not happy

I think a lot of this ties back in to that sense of entitlement I mentioned earlier. This guy has backed the project, and he now believes that this entitles him to more free stuff at regular intervals: at the time, the project was trending toward $300k, which would have meant 3 gems, 4 spells, and 2 relics (incidentally that’s the exact ratios for a standard marketplace), as well as 2 Nemesis and a Mage, all of which others would need to buy as a separate expansion (probably around $20), and a few extra dividers and basic Nemesis cards not available elsewhere. That’s on top of a base game that will now be slightly bigger and better quality for everyone than when the campaign launched.

Assuming they thought the game was worth the $65 tag when they backed it, it’s pretty hard to see how a backer could be unhappy with what they get here – the extra content and the value for money vs RRP are all fairly clear.

Too small unless stretched?

But of course, it is an assumption that they thought the original project was good value – I know that there have been KS campaigns in the past which I have looked at and decided that the basic pledge wasn’t worth my money.

Also, up until a Kickstarter project finishes, you can edit or cancel your pledge, without being committed to anything, so there are people who will jump in early, with a strong expectation of cancelling later on if the project doesn’t tick enough boxes for them along the way.

That seems a bit backwards to me, but as far as I can recall (it was a long time ago), I deliberated on the 9th World for a while, and backed it late on, having been swayed by the extra stuff they’d unlocked – if it had stayed in its pre-stretch goal state, I’d probably have kept my money.

Still there definitely are people who pledge early, do so without any real thought of backing out later, but who still bring their fairly subjective feelings about stretch-goals along, and demand to be heard.

I think that’s about enough on Stretch Goals for today. Next time in this KS mini-series, I want to continue the theme that we’re starting to touch on – the idea that being a Kickstarter backer somehow gives you “rights” that a mere buyer doesn’t have.

What I’ve decided to do then, is to turn this into a series of shorter articles, all of which I’m going to be lumping together under a Kickstarter sub-heading here on the blog: hopefully this will reduce the need for me to keep repeating myself in future, and allow people to dip in and out of the sections that most appeal to them.

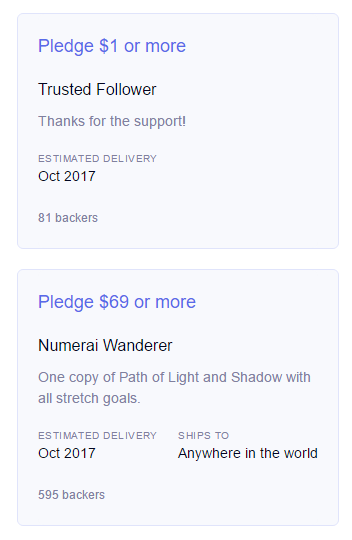

What I’ve decided to do then, is to turn this into a series of shorter articles, all of which I’m going to be lumping together under a Kickstarter sub-heading here on the blog: hopefully this will reduce the need for me to keep repeating myself in future, and allow people to dip in and out of the sections that most appeal to them. Kickstarter is a platform that allows people to create projects and ask other folk to “back” them, by pledging money. Most Kickstarter projects will run for about a month, and they will have a target in terms of the money they need to raise in order for the whole thing to be “funded” and go ahead. They generally have a number of “pledge” levels, where people are encouraged to offer a set amount of money towards the project and in return they are promised a particular “reward” at the end of things.

Kickstarter is a platform that allows people to create projects and ask other folk to “back” them, by pledging money. Most Kickstarter projects will run for about a month, and they will have a target in terms of the money they need to raise in order for the whole thing to be “funded” and go ahead. They generally have a number of “pledge” levels, where people are encouraged to offer a set amount of money towards the project and in return they are promised a particular “reward” at the end of things.

Other campaigns avoid Pledge Manager. The most recent project I backed, Aeon’s End: War Eternal kept giving us large reminders that we needed to have pledged for the full cost of the stuff we wanted by the time the campaign ended, as that would be it. Instead, we got an electronic survey to indicate what the money was for.

Other campaigns avoid Pledge Manager. The most recent project I backed, Aeon’s End: War Eternal kept giving us large reminders that we needed to have pledged for the full cost of the stuff we wanted by the time the campaign ended, as that would be it. Instead, we got an electronic survey to indicate what the money was for.

April had always seemed like it would be the month where I got to 10 of 10 – a fairly long way ahead of last year. I was on 8 of 8 at the end of March, and most of those 8 were already at 10 plays. Playing Legendary once more, managing to get in another couple of games of Eldritch Horror (new expansion for my birthday), and making it along to Destiny night for the first time in ages all had me right on the cusp.

April had always seemed like it would be the month where I got to 10 of 10 – a fairly long way ahead of last year. I was on 8 of 8 at the end of March, and most of those 8 were already at 10 plays. Playing Legendary once more, managing to get in another couple of games of Eldritch Horror (new expansion for my birthday), and making it along to Destiny night for the first time in ages all had me right on the cusp.

There were a few noticeable shifts in April, games which found new games, new avenues of play, or whole areas opened up like Pandora’s Box. Most of them, however, I’m going to leave for another time – games that have only just arrived, or which warrant articles of their own. In this new, baby-filled world, I don’t want to promise anything, but I’m hoping that those articles are going to be ready sometime in May (or June, or later…)

There were a few noticeable shifts in April, games which found new games, new avenues of play, or whole areas opened up like Pandora’s Box. Most of them, however, I’m going to leave for another time – games that have only just arrived, or which warrant articles of their own. In this new, baby-filled world, I don’t want to promise anything, but I’m hoping that those articles are going to be ready sometime in May (or June, or later…)